Fridge Magnets and Memory: Part 1

Jun 20,2025

Jun 20,2025

Pu You

Pu You

I was getting a glass of water at a friend-of-a-friend’s party when I noticed their fridge. Or rather, what was on it. Every single magnetized inch of it was covered in souvenir refrigerator magnets. They came from every continent and from many of the planet’s better-known islands, and they had been lovingly selected for maximum heinousness. A neon-green palm tree against an ineptly-painted sunsetted sky (for Florida). Plastic simulations of Taiwanese dim-sum and googly-eyed camels. There was a thermometer with the Dubai skyline printed on it, and a wooden depressive looking lion from Kenya, and an Australian boomerang with a startled kangaroo drawn on it . And more, so much more.

I stood there losing myself in my magnets for a moment, imagining the places that they came from, the particular trips that they represented, and also what sort of human being thought that making magnets shaped like screaming lobsters was a path to success in tourist retail.

"My wife collects them from everywhere she goes. She likes them more if they’re ugly,” said the friend-of-a-friend in a resigned sort of way, as he noticed me noticing the magnets. The wife in question was away on business at the time of the party and I knew she was a highly successful, sophisticated person. And yet, she had lovingly curated this refrigerator display of the most disreputable, crapbucket package-drinking-tour souvenirs that I’d ever laid eyes on within a private home. I hadn’t met her, but I felt in that moment as if I understood her a bit. She was the kind of person who travels the world on important business, and returns to her family with the gift of a metallic rainbow alligator magnet that can also open a beer.

Her fridge inspired me, altered my previously untargeted souvenir-buying habits. Today, years after I first saw her kitchen, I too am a Person Who Has Magnets, dozens and dozens of them, taking up every empty patch of metal on my fridge. I buy them whenever I go anywhere beyond my immediate metro area. My magnets hail from dozens of countries and states and cities and tourist attractions, and just like my unseen magnet-hero, I select them for maximum horribleness, luridness, ambition. I have become what Russian magnet-fan Dmitry Balashov called a “memomagnetist” back in 2008,

And yet despite all this passion, I realized recently that I didn’t know anything about fridge magnets. I had no idea where they came from, or who invented them, or why they were ubiquitous in souvenir-junk shops around the entire planet. fridge magnet dates back only to the mid-1960s, yet they are found on every corner of the earth and sold in every souvenir shop and kitchen-goods store on the planet. They are outlandishly successful, and yet I discovered very little has been written on their history or their gigantic popularity.

Here, then, is the origin and current circumstances of that magnetic pink sea turtle you bought in the Bahamas and stuck on your fridge.

The Mysterious And Little-Known History of Your Stupid Fridge Magnet

Fridge magnets have not always existed. In fact, they are probably newer than many people think they are. Just as the invention of the car required the prior invention of the internal combustion engine, so too did fridge magnets require two antecedent technologies: cheap (“permanent”) magnets that don’t lose their strength over time, and home refrigerators.

Humanity has been generally aware of the concept of magnetism for thousands of years, as they observed naturally-magnetized materials in nature. What was trickier was imbuing something with permanent magnetism, which didn’t lose its power over time. In 1930, Drs. Yogoro Kato and Takeshi Takei invented a magnetic compound known as “ferrite,” which was initially used to produce radios. Ferrite magnets were considerably cheaper than the permanent magnets that came before it. In fact, they were so cheap that they could reasonably be used to produce junky souvenirs. (But they weren’t, just yet).

While mechanical iceboxes first appeared in the United States sometime after 1915, they were a fancy, luxury object, the sort of thing you’d purchase to signal your superiority over the poor peasants who still had to stick their perishable food in an old-fashioned icebox and hope for the best.

That all changed in the 1930s, as refrigerators became easier-to-produce and less expensive. Even amidst the misery of the Great Depression, American consumers began purchasing them in droves, attracted by (not inaccurate) marketing claims about how electrical fridges facilitated thriftiness and food safety.

By 1940, 50% of American households reported owning one, and by 1944, that figure had grown to a remarkable 85%. In just a few short decades, the electric refrigerator had become an essential element of the landscape of the American kitchen, an object that pretty much everyone had, or very much wanted to have in the near future. Yet these upwardly-mobile fridge owners of the 1940s and 1950s didn’t have fridge magnets. They hadn’t been invented yet, in large part because these early fridges often weren’t made with materials that magnets could stick to: many were finished in porcelain or plastic or wood.

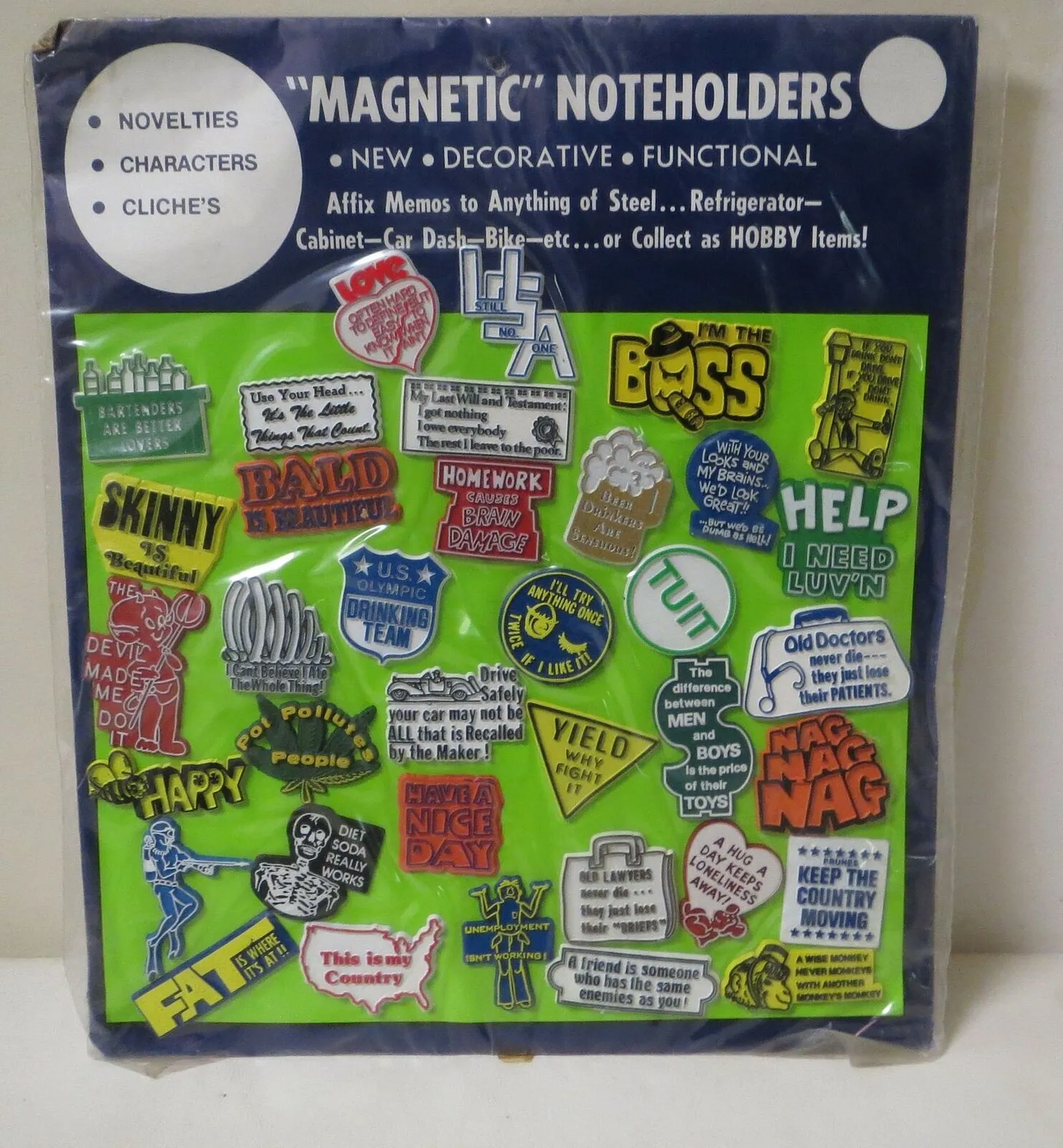

As time went by, American fridges began to grow more expansive in size, objects (available in charming avocado, harvest gold, or pink colors!) with ever-more unused space to put junk on. By the 1960s, the souvenir fridge magnet had both a cheap mechanism for sticking-to-things and a natural habitat. It just needed someone to invent it.

We like it when we can attribute the invention of a certain object or idea to a single human being, a solo genius struck with a sudden and remarkable flash of genius, a Great Man (and it is almost always a man) who rattles the course of history with his muscular ideas about automated can-openers or the cotton gin or drive-through fast food restaurants. And so it goes with fridge magnets.

Most sources, from academia to the Internet, attribute their invention to a man from St Louis named William Zimmerman, owner of the Magic Magnets company. As the usual, uncritical Internet story goes, Zimmerman at some point in the early 1970s patented a set of magnets that depicted cheerful cartoon characters, an innovation that would permit harried American families to hang up crayon drawings and stained takeout menus in a convenient nose-level location. It’s a superb little story, a pleasant mid-century Horatio Alger tale. It was also shockingly difficult to prove true.

I began my hunt for William Zimmerman with Google’s patent search, where I assumed that his great fridge-magnet-with-a-dog-on-it patent would pop up. To my surprise, I ran a search through their patent records for “William Zimmerman” and “refrigerator magnets” and came up totally empty-handed. The only patents on record granted to any William Zimmerman dated back to the late 1800s and early 1900: this particular Zimmerman was an ingenious sort of guy who had invented, among other things, a new kind of folding bed and something called a “smut-machine.”) But no magnets.

I could find nothing else on Google, or Google Scholar, or in newspaper records, and there were a lot of people named William Zimmerman wandering around the country doing newsworthy things in the 20th century. By this point, I had spent dozens of hours trying to hunt William Zimmerman, to prove that he had existed and fiddled around with magnets one way or another. I get sucked into these hunts for one-or-another poorly documented person on the Internet, sometimes. I guess it feels, in a way, like I am paying homage to their memory, doing my small part to ensure that they are not totally expunged from the world as I hunt for evidence that they really existed.

Then, it occurred to me that I should figure out when people first started talking about Zimmerman and his magnetic inventions.. On November 21, 2006, a Wikipedia user identified only by their IP address added a paragraph of information about William Zimmerman to the encyclopedia’s entry for “Fridge Magnet.” This person claimed – without citation - that Zimmerman not only patented the first fridge magnet in the early 1970s (which is well after the first fridge magnets I could find were produced), but that he “patented the first hi-fi record brush in the 1950s,” then used the proceeds from its sale to RCA to purchase two St Louis theme parks.

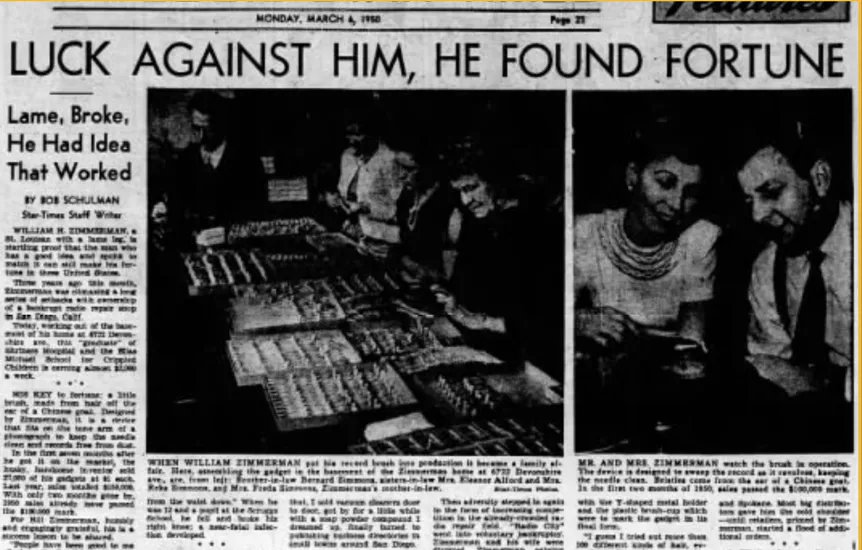

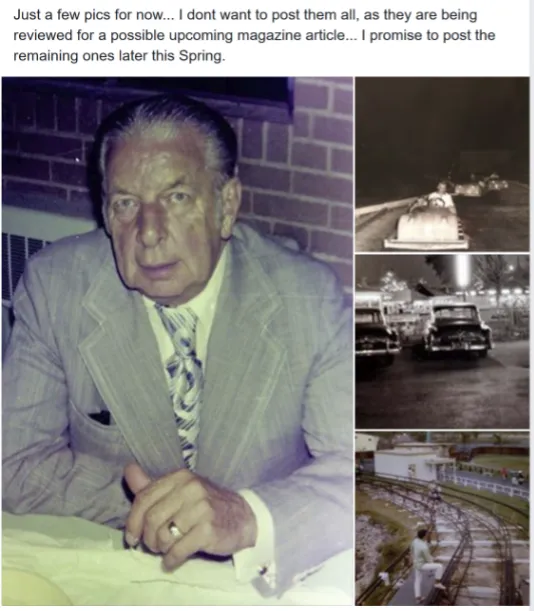

The theme parks. Finally, I was getting somewhere. I found that someone named William Zimmusic magnet,custom music fridge magnet,fridge beats magnet,fridge beats,soufeel fridge magnet,fridge magnet that plays music,mini vase fridge magnet,personalized fridge magnet,fridge magnet maker,magnet maker merman really does seem to have co-owned a couple of amusement parks in St. Louis, and I was able to find a 1948 patent for a magnetic “phonograph pickup arm” attributed to a William H. Zimmerman, and a St. Louis based record-brush firm named the W.H. Zimmerman Co. Amidst all those long-dead newspaper scans, I found a 1950 St. Louis Star-Times newspaper article about his record-brush exploits, and it even came with a photograph of the then-30 something Zimmerman and his wife.

The paper described him as a formerly “lame and broke” man who had turned into a “husky and handsome inventor,” a scrappy surv

ivor-type who had suffered a serious injury to his hip as a child that left him with a permanently stiff leg. He’d spent much of his youth in California trying everything from door-to-door vacuum sales to working in an aircraft factory, up until he came up with his great idea about record brushes (which were made with bristles improbably sourced “from the ear of a Chinese goat.”)

So William Zimmerman had lived in St Louis, and probably knew something about magnets, but I still couldn’t find any evidence that he’d done something with the kind that go on the fridge. Until I came upon a Facebook page dedicated to Holiday Hill, one of the long-since dismantled theme parks that he used to own. Dozens of people posted photographs of the theme park and the people who ran it, and one of those people had posted a sepia-tinged photograph of William Zimmerman, taken sometime in the 1960, unmistakably the same man as the one in the 1950 article.

CN

CN

HOME

HOME Functional Decoration With Amazing Fridge Magnets

Functional Decoration With Amazing Fridge Magnets  You May Also Like

You May Also Like

Tel

Tel

Email

Email

Address

Address